Robert Heinecken: Myth and Loss Reimagined, 2017 - 2019

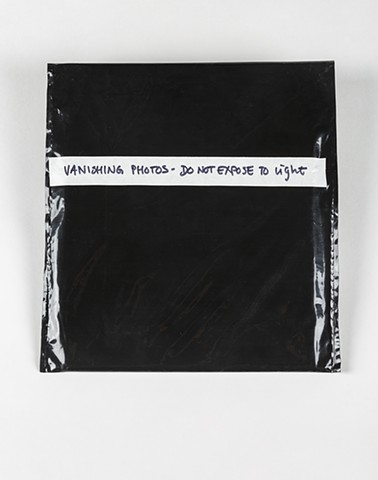

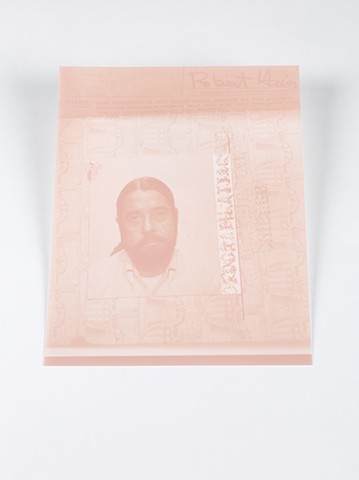

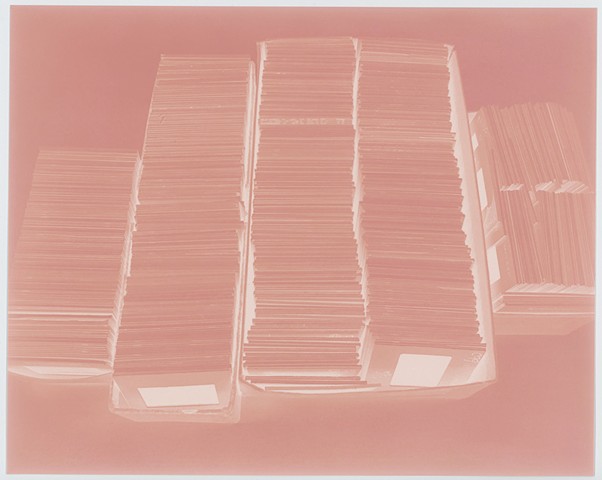

In 2017, I was awarded the Photographic Arts Council / Los Angeles Research Fellowship at the Center for Creative Photography to study Robert Heinecken, a 20th century visionary whose work speaks strongly to 21st century practitioners. My intent was to document objects from his archive that comment on the growing gap between the analog and digital era and how accumulation is changing at a time where collecting is less common and experiences dominate. I desired to learn more about Heinecken’s Vanishing Photographs, a series of unfixed images that gradually darkened when viewed in the light, and his cremated ashes stored in a saltshaker, as they are the most poignant examples that bridge the gap between analog and digital. These ephemeral items are enshrouded in myth and they contribute to his legacy and I wanted to hold them in my hands.

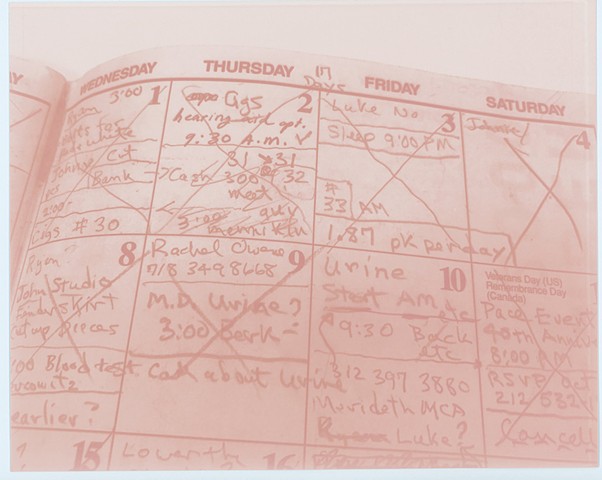

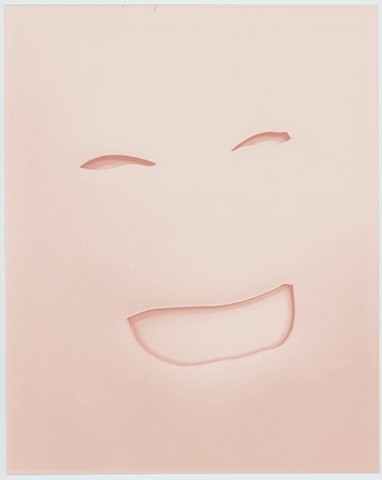

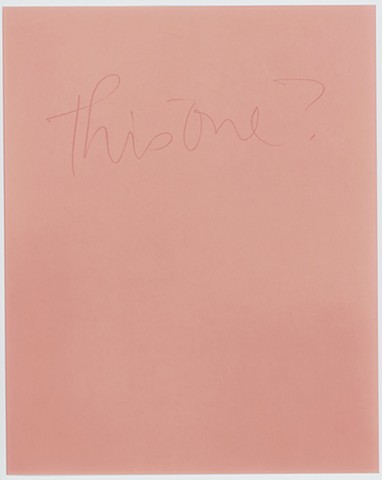

While in the archive, I made a discovery that altered my course and caused me to reconsider everything I thought I knew about him. While perusing fourteen VHS tapes of a 1995 seminar and two interviews as far back as 1975, I began to notice his memory loss and how it would eventually lead to Alzheimer’s disease. I lost count of how many times he said “I don’t remember” and watched in shock as he struggled to recall who was standing before him when the daughter of an old friend surprised him while being videotaped. My plan to create a contemporary version of his Vanishing Photographs shifted to recording objects in his archive that implied or overtly suggested absence. Evidence of his declining memory would redefine my series yet still comment on the shrinking role of analog practices.

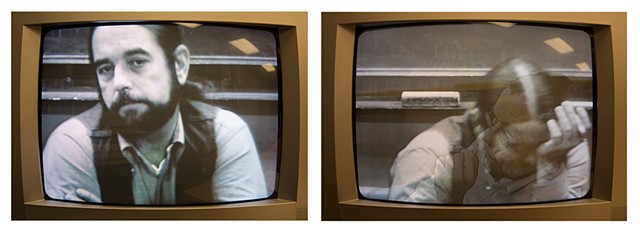

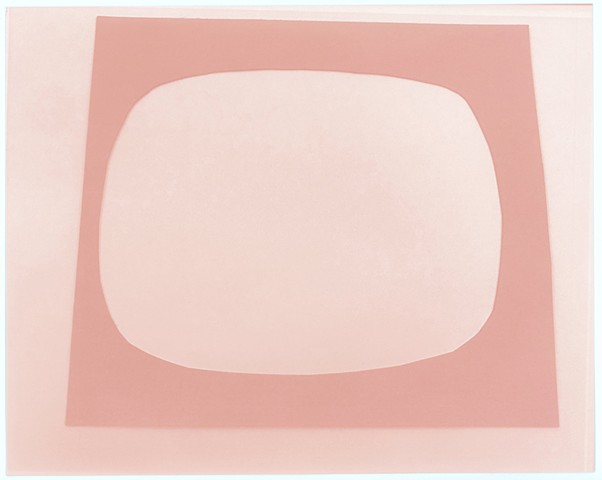

I let the objects dictate my direction and this resulted in the series expanding by two pieces. A diptych of stills from a television screen references Heinecken’s photographs of newswomen from 1984. An off-register image of his ashes printed as a positive and negative on transparency film sandwiched in Plexiglas recalls Venus Mirrored (1968). These exist alongside the lumen prints made with expired paper and digital negatives, exposed in the sunshine for 24 hours. Like Heinecken’s Vanishing Photographs, they remained unfixed. My documentation of his ephemera will slowly disappear if viewed in the light, an action relating directly to his memory loss.

Despite our radical differences in subject matter, Heinecken is instrumental to my artistic process. His disregard of the definition of photography, his use of appropriation, his employment of guerilla tactics in the distribution of altered magazines, and his experimentation with three-dimensional presentation first drew me to him. This experience allowed me to see how legacy and mythology are defined by the things left behind while continuing to explore themes of loss and absence from a new perspective.

Special thanks to Leslie Squyres and Emily Una Weirich of the Center for Creative Photography, the Heinecken Trust, Cass Fey, Kate Palmer Albers, Kelli Connell, Peter Happel Christian and Colin Edgington for their contributions to this series.